Far be it from me to pass myself off as an expert on Chinese literature in Malaysia, where one out of three people I meet on the street can prove my ignorance! Perhaps, reader, you may be interested how a western educated man views this great Asian tradition.

I am convinced that poetry, despite language and convention, is everywhere One. But a tragedy of modernity is the levelling of all differences to a banality that passes by the name of "western culture."

Even "higher" culture, now mostly dead, is being subjected to the grind. Soon (if not already) there will be a standardized Ph.D. thesis on everything, Murut ethnobotany and Brazilian gangster shoes. The heart of the world's mystery will be plucked out and pickled in academic prose.

The west plundered the east and cannibalized itself. Few know that things went the other way also. A few westerners were greatly impressed by eastern arts, and learned important lessons which they applied to their own native arts. Chinese poetry has had an enormous influence on English poetry.

I fell in love with Chinese poetry while at Yale. In my second year, I found myself sharing an apartment with Li Kai, a computer scientist from Beijing who has since gone on to become a professor at Princeton, and remains a dear friend.

Kai in his younger days was quite as good a man of letters as a scientist. He partly survived the Cultural Revolution by reading classical novels at home, and he had to hide his skills both at composition and calligraphy, lest his comrades put him to work writing loathsome revolutionary essays and inscribing slogans on banners in his fine hand.

There is a mystic appropriateness in a Chinese scholar's professing computer science. Computing was made possible by the invention of the binary notation, in which all numbers can be represented by ones and zeros. The German mathematician Leibniz invented binary numbers back in the 17th century, after he had seen the hexagrams of the I Ching. Did the classic intend that? Kai a truly cultured man in an entirely different tradition from mine but one that I felt sympathy for as soon as I met it, and understood in an intuitive way. Everything I think I really know about Chinese poetry, I owe to Kai.

In my reading of Chinese poetry in translation, I came across poems which I especially liked, but felt that the translators had not done justice to. The problem with translating Chinese poetry into English lies in the differing natures of the two languages. Classical Chinese operates through the root meanings of words: one syllable, expressed in one character, equals one idea.

English is a language whose grammatical mechanisms are highly elaborate. For example, in every English sentence, the verb must show the elements of number and tense, which the Chinese verb lacks. Chinese can be so concise because the writer can count on the reader to supply this information. English needs many more syllables than Chinese in order to say the same things.

Kai taught me to use the Chinese dictionary, gave me his volume of Three Hundred Tang Poems, and set me to work. I copied down each character, and spent about five minutes looking up each in the dictionary. Some characters, whose radicals are not obvious, took much, much longer to find. I then drafted a translation and showed it to Kai, who criticised it and read the commentary for me to see if there was anything I should know. Then I went back to correct it.

I began translating with the idea that Chinese poetry should be rendered into more or less normal English, with all the grammatical necessities. Later on I began to feel that a Chinese line, translated to a bare string of English words, seemed more beautiful than when it was expanded into proper English.

Kai approved my translations in this bare style and remarked, "this is the way Chinese poetry really sounds." The language of Chinese poetry, he said, was never any language that people spoke. Since I did not learn collquial Chinese, and at this time of life I don't think I ever will, this was news to me.

Kai explained that a Chinese reader gets a sequence of characters. The

reader's challenge is to extract their poetic meaning in exactly the same

way an English reader must when faced with a string of words without explicit

grammatical connections. This knowledge delighted me no end. Here, I thought,

was a truly poetic language, freed from the tyranny of grammar, coming close

to conveying pure meaning!

My favorite Chinese poets are those that the Chinese have recognized

as their greatest: Li Bai, Du Fu, Su Tung Po, all greatest hits. I feel

as silly saying this as a Chinese reader might if he declared his favorite

English poet was Shakespeare. But perhaps the reason why I love them will

be new and interesting to one within the Chinese tradition: Chinese poetry

is lonely. Du Fu, for example, does not have the western sense of tragedy,

but he expresses the feelings of a man who knows himself to be alone amid

the world and in nature, or as Li Ho saw, alone in the midst of endless

time.

Chinese civilization I think may put more value on man's obligations to society than any other. But sensitive Chinese, brought up in that rigid system, knew well and early its limitations, the truth of what the anthropologist Lévi-Strauss says, that society never gives back as much as it demands. While less intense cultures are perfectly happy within themselves, and their poetry never passes the limits of the norm, Chinese poets looked beyond and saw the worth of the human being alone with his own feelings.

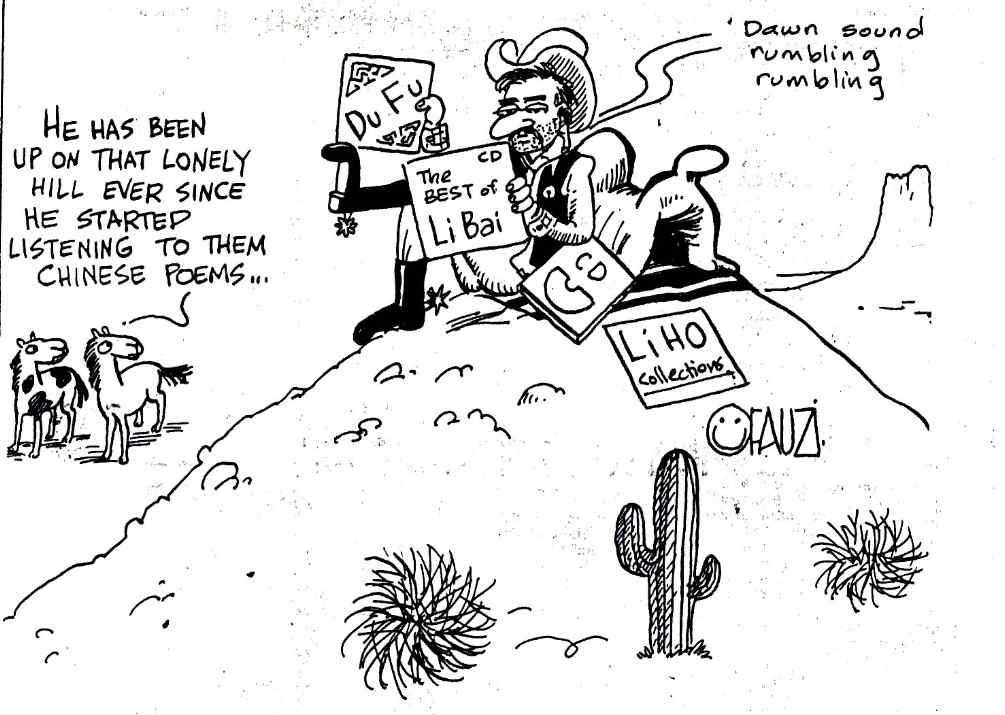

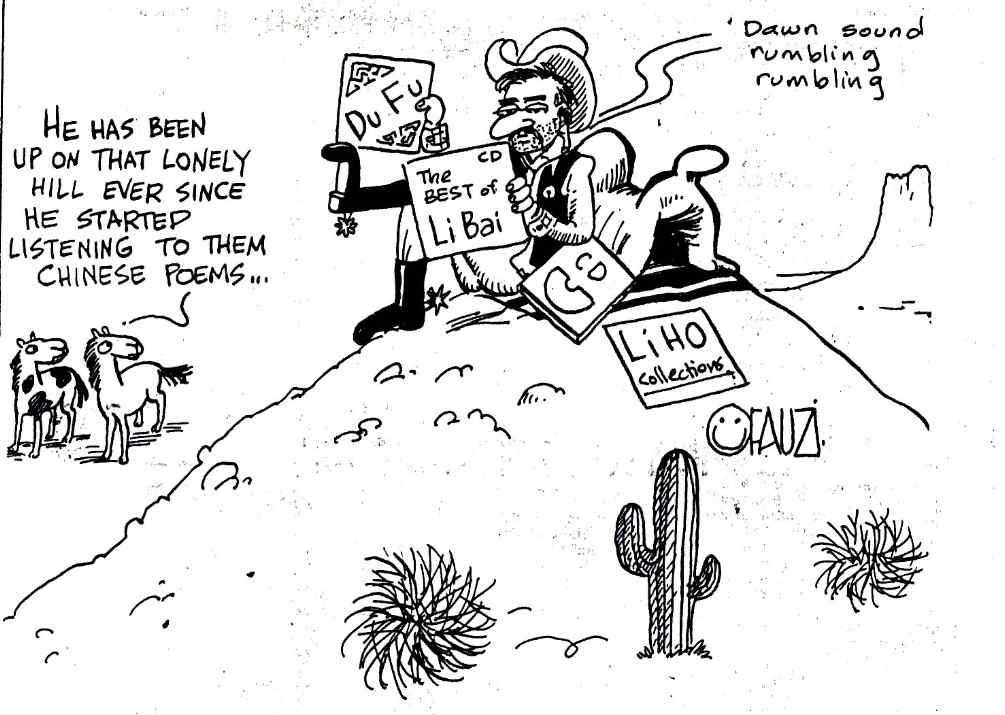

Great Chinese poetry has always been on the side of the loser, the man who stands apart from society, a strange situation in a land where literacy was the only ticket to power in the manadarin hierarchy. But Meng Chiao wrote "Bad poetry makes you an official. / Good poetry leaves you on a lonely hill." Another scholar I met told me that the place of poetry in Tang China was not so much different from now: few cared.

In a country of words, the poets saw beyond the words, the feeling that

lay behind them. Chinese poets, happy in their language, could dispense

with normal grammar, and I think they wanted even to get away from language,

to reach the pure poetic idea.

If civilization or human culture has produced anything good that sums

up and goes beyond its own values, it must be Chinese poetry.

Li Ho: Drums in the Street of Officials

Dawn sound

rumbling rumbling

hurries the turning sun.Dusk sound

rumbling rumbling

hurries the moon rising.Within Han walls

yellow willows

reflect on new curtains.In a cypress mound

Flying Swallow's

fragrant bones buried.Drums have shattered

a thousand years'

suns always white.Emperor Wu and

Qin's emperor

cannot hear them.From, sir,

sapphire hair

reed-flower white.Alone the ranged

South Mountains

watch over China.How many cycles

in Heaven above

the Immortals given funeral?The waterclock's sound

drip pressing drip

nothing breaks off.

| BACK |

INDEX |

NEXT PAGE |